Freedom in the World - Bahrain (2007)

Population: 700,000

Capital: Manama

Political Rights Score: 5

Civil Liberties Score: 5

Status: Partly Free

Trend Arrow

Bahrain received a downward trend arrow due to new legal restrictions on freedom of assembly.

Overview

In November 2006, the Kingdom of Bahrain held parliamentary and municipal elections that were mired in controversy. Accusations mounted over political naturalization of foreigners and gerrymandering of electoral districts before the elections to sway the vote in favor of the Sunni minority. Islamist parties were victorious in the lower house, claiming 30 out of the 40 seats, with the Shia party Al-Wefaq winning 17. Meanwhile, legal revisions pertaining to curtailing freedom of assembly, banning the defense of detainees, and continued censorship of the internet reversed steps to advance civil liberties.

The al-Khalifa family, who has ruled Bahrain for more than two centuries, comes from Bahrain’s minority Sunni Muslim population in this mostly Shiite Muslim country. Bahrain gained independence in 1971 after more than a hundred years as a British protectorate. The country’s first constitution provided for a national assembly with both elected and appointed members, but the king dissolved the assembly in 1975 for attempting to end al-Khalifa rule; the al-Khalifa family ruled without the National Assembly until 2002.

In 1993, the king established a consultative council of appointed notables, although this advisory body had no legislative power and did not lead to any major policy shifts. In 1994, Bahrain experienced protests sparked by arrests of prominent individuals who had petitioned for the reestablishment of democratic institutions such as the National Assembly. The disturbances left more than 40 people dead, thousands arrested, and hundreds either imprisoned or exiled.

Sheikh Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa’s March 1999 accession to the throne following his father’s death marked a turning point in Bahrain. Hamad released political prisoners, permitted the return of exiles, and eliminated emergency laws and courts. He also introduced the National Charter, which set a goal of creating a constitutional monarchy with an elected Parliament, separation of powers with an independent judicial branch, and rights guaranteeing women’s political participation.

In February 2001, voters overwhelmingly approved the National Charter. However, the process of political reform ultimately disappointed many Bahrainis by the time local and parliamentary elections were held in May and October 2002, respectively. Leading Shiite groups and leftists boycotted these elections, protesting political campaigning restrictions and electoral gerrymandering aimed at diminishing the power of the Shiite majority. Sunni groups won most of the seats in the new National Assembly. Despite the boycott, opposition groups fared well at the polls, and the new cabinet included opposition figures.

On November 25, Bahrainis participated in parliamentary and municipal elections. Shiite groups that boycotted the last election decided to take part. Al-Wefaq, the Shiite political society, submitted 19 candidates to contest seats, but no women were on their list. The results went overwhelmingly to the Islamist parties, with 30 out of 40 seats in their favor. The remaining 10 were awarded to the liberal candidates. Al-Wefaq, in particular, won a total of 17 seats with 42 percent of the vote. King Hamad appointed a liberal Consultative Council, the upper house of the bicameral Parliament, to offset the overwhelmingly Islamist Council of Representatives, or lower house. Scandals emerged in the wake of the elections surrounding claims that a secret group within the government led by a senior official was determined to keep the Shiite majority unrepresented. Further accusations were made with regard to increased naturalization both of foreign workers and other Arabs in advance of the elections, supposedly with the intent of increasing the number of Sunni voters. Meanwhile, the Bahrain Transparency Society monitored the electoral process and campaigns and established a telephone hotline to report irregularities in the poll process. The elections were considered generally free and fair by civil society groups, and turnout was reported at 61 percent.

In December 2006, Bahrain appointed former minister Jawad Oraied as the country’s first Shia deputy prime minister. Also, Dr. Nizar al-Baharna, a former member of Al-Wefaq, was appointed minister of foreign affairs in a cabinet reshuffle the same month.

In January 2006, the U.S.-Bahrain Free Trade Agreement was formalized.

Political Rights and Civil Liberties

Bahrain is not an electoral democracy. Bahrain’s 2002 constitution gives the king power over the executive, legislative, and judicial authorities. He appoints cabinet ministers and members of the 40-seat Consultative Council, the upper house of the National Assembly. The lower house, or Council of Representatives, consists of 40 popularly elected members. The National Assembly may propose legislation, but the cabinet must draft the laws. A July 2002 royal decree forbids the National Assembly from deliberating on any action that was taken by the executive branch before December 2002—the date the new National Assembly was inaugurated.

Formal political parties are illegal in Bahrain, but the government allows political societies or groupings to operate and organize activities in the country. In August 2005, the king, Sheikh Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa, ratified a new political associations law making it illegal to form political associations based on class, profession, or religion and requiring all political associations to register with the Ministry of Justice.

Although Bahrain has some anticorruption laws, enforcement is weak, and high-ranking officials suspected of corruption are rarely punished. Bahrain was ranked 36 out of 163 countries surveyed in Transparency International’s 2006 Corruption Perceptions Index.

Freedom of expression is limited in Bahrain. The government owns all broadcast media outlets, although the country’s three main newspapers are privately owned. In May 2006, the Minister of State for Cabinet Affairs warned that all reporting should be documented with known sources. In July, Bahraini authorities blocked access to Google Earth, Maps, and Video. While these restrictions were removed after some lobbying efforts, the government continues to control access to opposition and human rights websites and to censor access to blogs. These activities were stepped up in advance of the parliamentary elections and amid the scandal over an alleged anti-Shia conspiracy in the government.

Islam is the state religion. However, non-Muslim minorities are generally free to practice their religion. All religious groups must obtain a permit from the Ministry of Justice and Islamic Affairs to operate, although the government has not punished groups that have operated without this permit.

Bahrain has no formal laws or regulations that limit academic freedom, but teachers and professors tend to avoid politically sensitive topics and issues in the classroom and in their research. Bahrain has ambitions to be the regional education hub in the Gulf and announced in December 2006 the establishment of a $1 billion Higher Education City. The project aims to turn the education sector into a major industry by attracting international universities to the country, including a U.S. university, as well as an international center for research, housing, and entertainment and sports facilities.

In July 2006, the Consultative Council removed protections for freedom of assembly. Citizens must obtain a license to conduct demonstrations, rallies, and marches, which are now banned from sunrise to sunset in any public arena. The new legislation further stipulates that protesters are forbidden to carry any weapons, flammable products, or sticks.

Bahrain has seen strong growth in the number of nongovernmental organizations working in charitable activities, human rights, and women’s rights, but restrictions remain on these groups. The Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR) was closed and dissolved by the government in September 2004, and its executive director, ‘Abd al-Hadi al-Khawaja, was arrested after he criticized the prime minister and the government for their performance on poverty and economic rights; the center resumed activities in 2005. In a continuing battle, the Ministry of Social Development has threatened to pursue legal action against a number of civil and human rights groups who are operating without permits. The 1989 Societies Law prohibits any society from operating without an official permit.

Bahrainis have the right to establish independent labor unions without government permission. A royal decree giving workers the right to form labor unions also imposes limits, including a two-week notice to the company before a strike and a prohibition on strikes in vital sectors such as security, civil defense, transportation, hospitals, communications, and basic infrastructure. The law gives workers the right to strike after a strike action is approved by three-quarters of union members in a secret ballot. A new amendment to the labor law passed in October 2006 stipulates that private sector employees can no longer be dismissed for union activities. The decree instructs courts to reinstate the employee and orders the employer to compensate the employee for the period spent out of work when it is proven that the dismissal was based on union activities.

The judiciary is not independent of the executive branch. The king appoints all judges, and courts have been subject to government pressure. In the spring of 2005, Bahrain announced a plan to reform its judicial system, with measures to improve court efficiency to make trials quicker. The Ministry of the Interior is responsible for public security within the country and oversees the police and internal security services, and members of the royal family hold all security-related offices. In 2005, the government proposed new antiterrorism legislation that provided the death penalty for terrorist groups and jail terms for those who use religion to spread extremism. This legislation has been criticized with the warning that its interpretation of terrorist crimes was too broad and would lead to a heightened risk of torture and arbitrary detention. Bahraini police are reputed to often use excessive force to disperse crowds and contend with detainees. However, living conditions within prison facilities have greatly improved. Prisoners are permitted to make weekly phone calls to their families, and prisoners of all faiths have access to holy books and priests.

Although Shias constitute a majority of the citizenry, they are underrepresented in government and face discrimination in the workplace. Over the past five years, Bahrain has taken steps to integrate stateless persons, known as bidoon and consisting mostly of Shias of Persian origin, into the country, offering citizenship to several thousand. Nevertheless, bidoon and citizens who speak Farsi as their first language continue to face some social discrimination and special challenges finding employment.

Although women have the right to vote and participate in local and national elections, they are underrepresented politically. Before 2006, no woman had been elected to office in municipal or legislative elections. In the latest parliamentary elections, 18 women sought positions. One candidate, Lateefa al-Gaood, won her seat as there were no other candidates in her district. Five women ran in the municipal elections, but none won office. In January 2005, the king swore in a new cabinet, including Fatima al-Balushi as Minister of Social Affairs, who became the second female minister in Bahrain’s history. In June 2006, Haya Rasheed al-Khalifa was elected president of the UN General Assembly, and Mona al-Kawari was appointed the first female judge in the kingdom as well as in the Gulf region. Women are generally not afforded equal protections under the law.

In December 2006, the government announced plans to introduce unemployment benefits that would provide $400 per month to jobless Bahrainis, most of whom are women. The bill had yet to be implemented by year’s end. Eighteen thousand Bahrainis were expected to benefit from this new measure.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

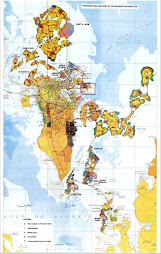

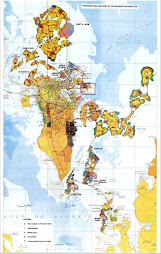

خارطة البحرين الجديدة

Facebook Badge

Followers

فسيلة السنكيس

متى ما ظهرت الفسيلة - الصغير من النخل- من فوق سطح الأرض، فمن حقها أن تنمو وان تعانق السماء دون حصار أو مضايقة أو استهداف

حق الفسيلة في الحياة كحق غيرها، من المخلوقات، خاصة وإن كانت دليل أصالة شعب كشعب البحرين

--------------------------------------------------------------

صاحب المدونة: د.عبدالجليل السنكيس

ناشط، كاتب وباحث أكاديمي من البحرين

البريد الإلكتروني: asingace@gmail.com

مدونة اخرى: http://alsingace.katib.org/

هاتف:8179-3966-973+

حق الفسيلة في الحياة كحق غيرها، من المخلوقات، خاصة وإن كانت دليل أصالة شعب كشعب البحرين

--------------------------------------------------------------

صاحب المدونة: د.عبدالجليل السنكيس

ناشط، كاتب وباحث أكاديمي من البحرين

البريد الإلكتروني: asingace@gmail.com

مدونة اخرى: http://alsingace.katib.org/

هاتف:8179-3966-973+

مواقع ووصلات ذات صلة Links of Interest

صور معبرة

خارطة البحرين الجديدة