MIDDLE EAST NEWS

JUNE 20, 2009

U.S. Navy Fleet's Mideast Home Is Facing Rise in Sectarian Strife

By YAROSLAV TROFIMOV

MADINAT HAMAD, Bahrain --

On a recent evening, Issa al Jibb climbed the roof of his home and started hurling Molotov cocktails into the adjoining property of the Rawi clan. By the time Bahraini police shot him down with a rubber bullet, Mr. Jibb had managed to burn three cars and part of the building, and inflicted serious burns on two Rawi teenagers.

This was no ordinary feud among neighbors. Mr. Jibb, 46 years old, is a native of this small Persian Gulf kingdom. The Rawis are originally from Syria, were recruited along with thousands of other Arabs and Pakistanis to serve in Bahrain's security forces and eventually rewarded with Bahraini citizenship for their loyalty to the crown.

Hostility between these two communities is on the rise, with several other clashes, car torchings and beatings reported in recent months. "Bahrainis think that we just don't belong, that we're aliens to this area and to this state," says a Syrian-born army officer who lives nearby.

Yaroslav Trofimov/The Wall Street Journal

Freih al Rawi, originally from Syria, is one of the thousands recruited to Bahrain to serve in its security forces in exchange for citizenship there.

This was no ordinary feud among neighbors. Mr. Jibb, 46 years old, is a native of this small Persian Gulf kingdom. The Rawis are originally from Syria, were recruited along with thousands of other Arabs and Pakistanis to serve in Bahrain's security forces and eventually rewarded with Bahraini citizenship for their loyalty to the crown.

Hostility between these two communities is on the rise, with several other clashes, car torchings and beatings reported in recent months. "Bahrainis think that we just don't belong, that we're aliens to this area and to this state," says a Syrian-born army officer who lives nearby.

Yaroslav Trofimov/The Wall Street Journal

Freih al Rawi, originally from Syria, is one of the thousands recruited to Bahrain to serve in its security forces in exchange for citizenship there.

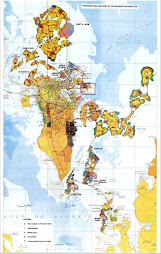

Once hailed for its democratic reforms, Bahrain -- a strategic island-state that serves as headquarters of the U.S. Navy Fifth Fleet -- is increasingly rocked by sectarian and ethnic strife. Though the majority of Bahrain's 530,000 citizens are Shiites, power remains in the hands of a Sunni royal family, the only such minority regime in the Arab world since the downfall of Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Suspecting its Shiite citizens of loyalty to nearby Iran, the island's former master, Bahrain's royal family has long relied on Sunni mercenaries from countries such as Syria, Jordan, Yemen and Pakistan to staff Bahrain's army, police and security service.

Earlier this decade, as Washington pushed for democratization in the region, Bahrain's King Hamad freed political prisoners and established an elected parliament with limited powers. However, opposition leaders and some independent analysts charge, a parallel program began at the same time, largely ignored by Western nations that depend on Bahrain's valuable naval facilities. The regime, they say, has sharply accelerated its policy of naturalizing Sunni mercenaries, aiming to inflate the size of the Sunni electorate -- and to defuse Iran's growing influence.

"There seems to be a clear political strategy to alter the country's demographic balance in order to counter the Shiite voting power," says Toby C. Jones, professor of Middle East studies at Rutgers University and a former Bahrain-based analyst at the International Crisis Group think tank. "This naturalization stuff is a time bomb."

Bahraini officials deny any such policy exists, and insist there is no discrimination against the country's Shiites. According to Bahrain's interior minister, Sheik Rashid bin Abdullah al Khalifa, only about 7,000 people were naturalized in the past five years. Opposition politicians, however, calculate the naturalization's true pace at some 10,000 people a year, based on voter registration statistics -- a big number in such a small country.

People picked for this naturalization "aren't just Sunnis," but religious fundamentalists "who share the hatred of the Shiites," asserts Hassan Mushaima, leader of Bahrain's Haq Shiite movement who was imprisoned for three months this year for his role in violent street protests.

Not just Bahraini Shiites oppose the naturalization. Initially, the island's Sunnis welcomed fellow Sunni newcomers, says Ebrahim Sharif Alsayed, secretary- general of the Waad secularist movement and a Sunni himself. "But today, most Sunnis are strongly against the naturalization," he says. "It's not about balancing the Shiites anymore -- it's about protecting the indigenous Sunni population from being invaded by foreigners."

Mr. Jibb, the Bahraini who threw Molotov cocktails into his neighbors' home in Madinat Hamad last month, is a Sunni, too. The conflict began in December, when Mr. Jibb witnessed the beating of a Bahraini neighbor by the Rawis and other naturalized Syrians, according to his sister Leila. "The Syrians, they're like a gang trying to control the whole area, bullying the whole street just to show who's the boss," she says.

A few days later, the Rawis attacked Mr. Jibb with a hammer blow on the head, prompting a hospitalization, she says. Members of the Rawi household, headed by retired Bahraini army sergeant Freih al Rawi, and comprising some 40 people, deny they instigated the clash. "We know; there's bad feeling for foreign people here," says one of Mr. Rawi's sons, an army officer.

The night of May 29, Ms. Jibb says, her brother -- who suffered psychiatric problems after the December hammer blow to the head -- found himself the target of taunts by the Rawis again, and simply "lost his mind," unleashing the volley of Molotov cocktails. Ms. Jibb has since fled her house, fearing revenge from the Syrian-born neighbors.

"How can it be?" she wondered indignantly. "I, a pure Bahraini lady, am now homeless in my own country